“One of the functions of art is to give people the words to know their own experience. Storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want.”

- Ursula K. Le Guin

The stories we tell ourselves, about both our public and private pasts, determine so much of how we will show up for the present. How we interpret experiences has a profound impact on our capacity for both agency and compassion, and subsequently our personhood. The relationship between agency and victimhood is a nuanced one, and how we live our lives may be determined by the lens through which we view our own narrative and the ways in which we tell those stories.

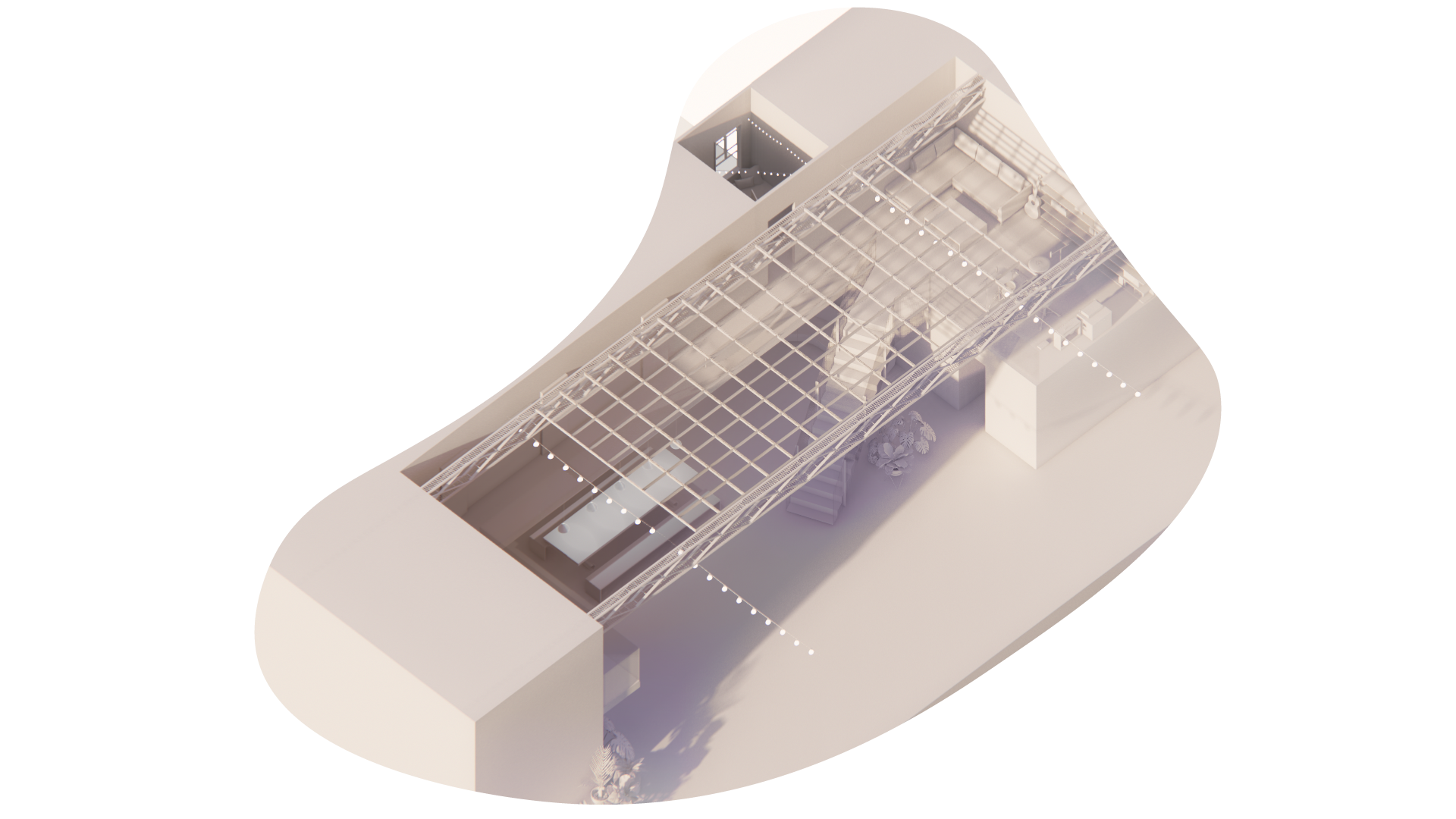

The narratives we construct around our own experiences not only constitute the deeply personal epistemological scaffolding which come to inform our worldviews, but also the lens through which we view that very world. The capacity to interpret, assimilate, and often cope with past experiences holds great bearing on the way in which we move through the present and what we are able to conceive as possible for the future. This has profound implications for both our individual and collective lives, and thus our ability to engage embodied change and sustained transformation on a societal level. In order to enact equitable, pluralistic, and reparative futures, we must first believe they are possible. In this effort, the importance in politicizing trauma1 is paramount given the immediate threat climate change and systemic violence pose to frontline communities2. “Enacting Just Futures” examines urgent questions3 about the human condition in crisis through storytelling. “Enacting Just Futures” takes the form of a screenplay; a speculative and visionary fiction4 that seeks to empower adaptive agency in order to collectively enact a new world order6. I use fiction as a means to challenge the relationships between crypto-colonialism7, capitalism, and climate change that systematically subjugate communities that do not subscribe to their ideologies8.

A society’s capacity to usefully integrate tragic compassion9 as a structural tenet hinges upon philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s insight that “people are dignified agents, but they are also, frequently, victims”. That victimization, catalyzed by environmental degradation, will become rampant for millions10 as we enter an age of unprecedented insecurity in a truly anthropogenic era where no part of earth - whether directly or indirectly - has been untouched by the impact of mankind12. In order for those most disenfranchised to be treated with dignity, the collective narrative for activists seeking to dismantle systems of oppression needs to shift from resilience13 to resistance - we cannot keep asking the same vulnerable communities to absorb the risks and costs of this crisis.

“Can we really not imagine anything better?”

This question was first posed to me last spring by Collette Pichon Battle in a lecture on Leadership in Environmental Conflicts. It is one that I have since envisioned as the call to action of my graduate studies; one that requires both a realistic assessment of current political and economic systems, and a radical revisioning of what they could be. Addressing this question as a society will require organized, empathic leadership that promotes purposeful experimentation and prioritizes a just and inclusive process. In order for this undertaking of transformative justice to be successful, we will not only need creative strategies and tactics, but public narratives that inspire action in the face of uncertainty - ones that inspire hope. Hope alongside grief, fear, and anger - because all of those things coexist. Collette Pichon Battle’s lecture highlighted the failures of our collective moral imagination that have perpetuated oppressive, hegemonic systems through complacency. We have not been living by the question - can we not imagine anything better?

We are surrounded by evidence of tremendous suffering, yet too often those with the ability to create positive change are complacent or impaired by empathic distress rather than striving to embody radical hope. I take inspiration from activist-scholars such as Rebecca Solnit, who reframe ideas of hope in terms of transformative solidarity that requires action. Transformative away from the status quo rather than reactionary and protective of it. This piece is about the self-work of interrogating our own narratives, ones where we may play the role of bystander or victim, to become agents of change for ourselves and our communities. Personal and societal transformation is inseparable. We need to build our capacity to hold that complexity while organizing together. Can modeling generative conflict through empathic storytelling lead to collective action? Imagined scenarios that invite readers to look beyond individual experience to interrogate the social, political, and economic roots of trauma? This piece attempts to build an imperfect world15 that we can not only hope for, but realistically work towards. We cannot move on to envisioning radically different social configurations and material flows without confronting the colonial legacies we inherited and perpetuate in the daily productions of our lives.

“Transform yourself to transform the world.”

- Grace Lee Boggs

My personal trauma and socialization have led me to believe that I am inherently wrong: my ideas are wrong, my emotions are wrong, my personhood is wrong. Invalid, irrelevant, unimportant. I put tremendous effort into believing that my opinions and emotions are equally as valid as those of the next person, but my depression and anxiety warn me otherwise. My unstable upbringing led to a belief that I am incapable of grasping concepts that seem obvious to everyone else around me; a belief which is amplified in settings where people are posturing and constantly claiming space (i.e. Harvard and Movement spaces in general). Taking up any amount of space feels dangerous to me, and sometimes when I speak my mind or assert a claim my body reacts as if I am in physical danger even if my mind knows better. Pragmatism and reparenting can only take me so far when I walk into a room not only believing these things about myself, but being convinced that every other person has the same assumption. I bring this up because this deep-seated fear has been a barrier to engaging with activism broadly. In part, I have not known what I have to offer; a sense of self doubt that has heightened in organizing spaces where burnout is high and patience is low16. Spaces of resistance have sometimes felt just as siloed and exclusionary as academia. There is also a sense of self-sacrifice and martyrdom associated with committing one's life to the revolution that has further complicated my relationship with activism. What are the ways to find joy and the ability to be present despite a societal expectation that suffering is inherent to justice work and success?

My views on this shifted after reading adrienne maree brown. Her latest book, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, has convinced me that changing the world doesn’t just have to be another form of work, but rather can be regenerative, healing, and pleasurable. She posits that we settle for suffering and self-negation because of oppression; that oppression makes us believe that pleasure (for me, happiness without fear or shame) is not something that we all have equal access to. In order for activism to be sustainable, it must be generative, inclusive, and more than that, imaginative of a more just future which does not further replicate the fissures of the status quo. Movement should feel satisfying; a relationship between what we have to offer and what the Movement needs from us. Adrienne has taught me that misery and Movement shouldn’t feel synonymous. That is the sweet spot we should strive to occupy--the one that precludes the voice of doubt that tells us we have nothing to offer, or that what we have to offer isn’t enough. In order to find that sweet spot, we have to establish boundaries alongside our politicization and build our capacity for love and rigor simultaneously17. Logic alone doesn’t change behavior; an emotional call to action is necessary to push forward a new social philosophy. We cannot make moral decisions without emotional information - if we cannot experience emotion, we cannot experience values that orient us to the choices we must make18. As Angela Davis says, “the revolution must be irresistible.”

Cultivating self-knowledge is a prerequisite to empathy and living in community. Complexity of character19 and personhood is often flattened and made dichotomous by identity politics and the reductive nature of the roles we play (or that are assigned to us). Liberating ourselves from these identity traps is necessary in order to facilitate sustainable momentum in the face of crisis and injustice. This should happen through an individual and communal healing process that prioritizes those who have been generationally oppressed20. Organizing for this movement should be a liberatory practice and an act of resistance that allows our visions and our values to align over time. ”Enacting Just Futures” seeks to play a role in collectively growing our capacity for hope in order to organize against further oppression and cultivate communities of care.

“There is nothing radical about moral clarity”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

In order to craft the screenplay as a call-to-action for enacting just futures, I looked to the framework and organizing principles of the Green New Deal (GND)21. Over the past 2 years we have witnessed the unveiling of equitable and inclusive climate policy in the form of the GND, spearheaded in the states by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and The Sunrise Movement and by many others abroad.

The GND is a departure from previous climate policy in that it addresses the roles of multiple systems and institutions in creating and perpetuating the global climate crisis. It assigns blame directly and provides adaptable paths forward against incrementalism, austerity, and concentrated wealth and ownership. It explicitly rejects logics of perpetual growth and extraction that are ingrained in the foundational institutions and practices that determine how wealth is produced and distributed. It acknowledges that moving beyond market fundamentalism will require deep structural shifts - not only in how the economy is organized, but in what is perceived as possible in the dominant social imaginary.

I believe in a necessarily radical global Green New Deal. Radical in its swift and dramatic departure from business-as-usual and in its recognizing (and uplifting) the undervalued labor of care24. With COVID-19 and state efforts to ‘return to normal’, we are living through a historic moment that has exposed clearly that ‘normal’ for most of the global population is a constant state of crisis. It has exposed the politics of preordained inequality and predatory economics that have so tragically exacerbated not only the coronavirus crisis, but every pre existing inextricable crisis that undergirds it.

COVID-19 presents an awakening from the hypnosis of normality. Isolation during the pandemic has felt like the eye of a storm at times. A familiar vantage point as someone who grew up in Florida with hurricanes rather than snow days in my childhood. That calm window presents an opportunity to assess the damage while awaiting the storm’s imminent, unstoppable second wave. The next wave is on our horizon, and the impacts of systemic breakdown in the midst of this pandemic are incomprehensible without storytelling. We are in the eye of a storm. Will we succumb to an insidious ethos of individualism, or forge new trajectories of connection and support?